The data presented here are the product of exhaustive monitoring carried out by Ca-minando Fronteras 365 days a year. Working with migrant communities, rescue services, family networks and human rights defenders on the ground, we collect, confirm and systematise the necessary data.

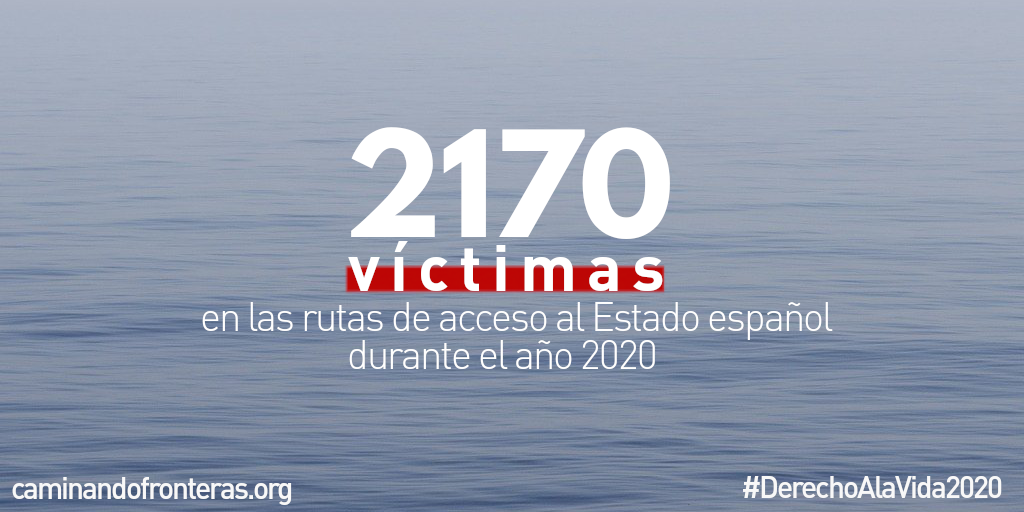

2020 was one of the most tragic, deadly years on the migration routes leading to the Spanish State via the western Euro-African border.

The prioritisation of migration control over the right to life was evident in the dismantling of various rescue services and the lack of coordination between them, rendering them increasingly unreliable. We also observed a lax response to calls for assistance, even when the vessels supplied their precise position. In some cases, delays in the response from rescue services led to entirely avoidable deaths.

The COVID-19 pandemic forced many people into exile to escape poverty and was a major factor in the mobility of people at the western Euro-African border in 2020. Meanwhile, the deterrence policies implemented by states, which contribute to increased revenues for the arms companies investing in migration control, led to the emergence of more dangerous routes with high mortality rates. For months, we warned of the impact on the right to life of the reactivation of the Algerian route in the Mediterranean and the Canary Islands route in the Atlantic:

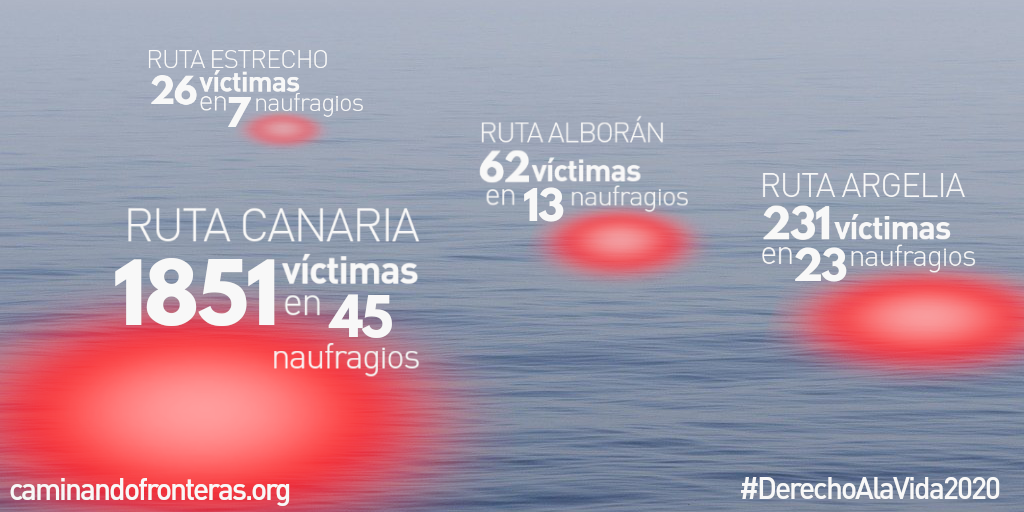

A) Algerian route: Large numbers of young people were driven out of the country by the wave of political persecution targeting members of the pro-democracy revolution and the high levels of poverty caused by the pandemic. The Algerian route is longer and more dangerous. Almería is the nearest destination on the route, but the Balearic Islands, Murcia and Cartagena pose far greater dangers due to the length of the journey. Usually, people call for help as they near the coast if their lives are in danger but the majority neglect to do so for fear of being returned to their countries of origin. As for the role of the Spanish State, search and rescue services are rarely mobilised. In the best-case scenario, the boats are intercepted by the Civil Guard, whose protocol focuses more on migration control than on saving lives at sea. At Ca-minando Fronteras, we have reconstructed the tragedies on this route using accounts from survivors and families in search of missing people.

B) Canary Islands route: The Canary Islands route departs from several different countries (Morocco, Senegal, Mauritania and Gambia), which makes it even more difficult to coordinate efforts to defend life between them. Even when this coordination was only bilateral, it already proved to be lacking. Regardless of the departure point, journeys on this route are extremely long and many boats go missing in the middle of the ocean. We have observed larger numbers of people departing from Mauritania, including many Malians following the coup d’état in Mali. In Senegal, young people’s calls for greater democracy and the decimation of their livelihoods by European fishing agreements drive them to an almost certain death on this migration route.

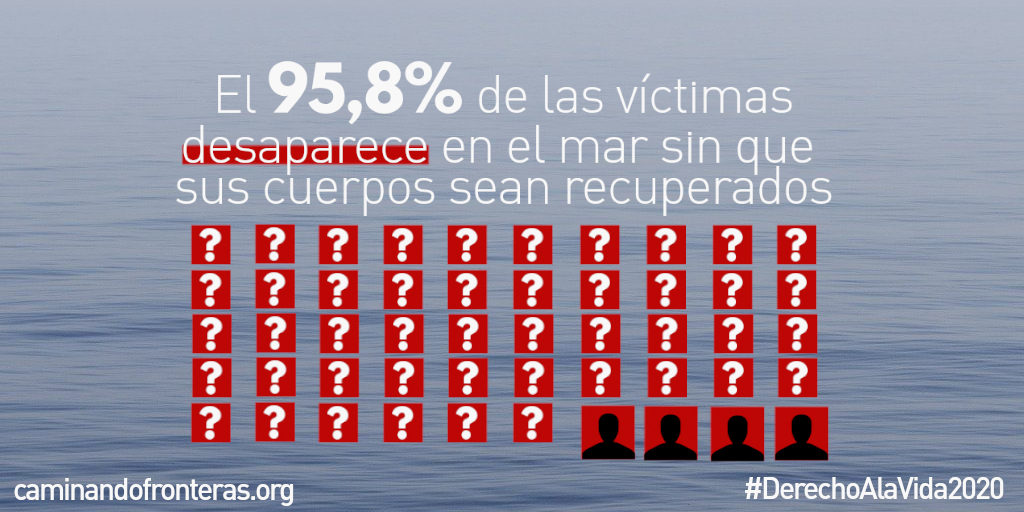

The criminalisation and persecution of people on the move have a major impact on mortality rates. Even their family members are criminalised, prompting them to delay reporting their loved ones missing and making it hard to launch an effective search operation. Senegal set a precedent when a father was imprisoned after his son died while attempting to migrate on a wooden boat. Families are stigmatised and blamed in migrants’ countries of origin, transit and destination. In the course of our work, we have received hundreds of complaints from family members who have been criminalised when visiting Spanish police stations to report someone missing at sea; in some cases, they were even prevented from exercising their right to make a report.

Our data are not perfect but they have been confirmed by fieldwork with migrant communities and families searching for their loved ones.

Despite the lack of transparency on these routes, we have been able to document numbers of dead and missing people via our Defending the Right to Life at Sea hotline and searches launched by numerous family members who have lost their loved ones at the borders and continue to demand the truth about what happened to them no matter what struggles they face.

This system of migration control, which only benefits the arms sector and criminal organisations, must be challenged in order to defend the right to life. At Ca-minando Fronteras, we call for:

- Improved coordination between search and rescue services and more material and human resources to defend human rights.

- Greater awareness among the actors involved in rescue missions, reception operations and identification of missing people.

- An end to the criminalisation of migrant self-organisation, which offers ways to reduce mortality rates.

- An end to the criminalisation of families seeking to protect the lives of their loved ones. Missing people have the right to be searched for and the dead are entitled to be identified, have their families informed and be given a decent burial.

- Recognition of border victims by states and introduction of channels to supply families with information.

The struggles of people on the move are aimed at defending life against the perverse interests of states.